Really, I Did Know

By Patrick F. Cannon

You could be forgiven for thinking, based on what you hear from the New York Times and many others, that children of past generations had never been taught that there was such a thing as slavery; or, if they were, that it might have been just a lifestyle choice.

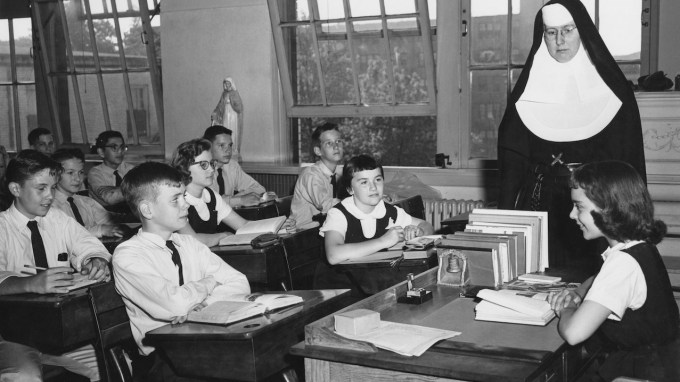

I just turned 84. Now, I can’t precisely recall how it was taught in the Roman Catholic grammar schools of Pittsburgh and Chicago, but I certainly got the impression that slavery was a bad thing, and that the Civil War was largely fought to eliminate it. Now, I don’t know what kids in Mississippi were taught, but I wouldn’t doubt that it was couched in a somewhat different way.

In public high school in McKeesport, PA, the teaching of American history became a bit more sophisticated. Two things became clearer – much of the politics of the first half of the 19th Century in the United States revolved around what to do about slavery; and also how to remove the indigenous peoples from land the settlers wanted to land they didn’t. Maybe Mississippi extolled the South’s Jim Crow laws as enlightened, but Pennsylvania certainly did not.

At Northwestern University, I took the usual lecture course in American history, which delved into these and other matters in more detail. While it explored the economic and social factors that led to the widespread use of slave labor in the south, it never confused reasons with excuses. Nor did is shy away from detailing the shameless way the country “solved” its indigenous peoples problem by penning them up in arid wastelands.

Since then, I have read widely in American history. These issues and many more have been explored in detail in countless books by dedicated scholars (and some not quite so dedicated to the truth, one must admit). The point is: no one who cares to spend a little time studying American history can deny that slavery in particular hasn’t been extensively and truthfully studied and written about. But until recently, I was never personally told that whatever successes I might have had in my life were based upon the simple fact that I was white; and that I was a member of the “privileged” class.

This is not to deny that privilege has played a role in the relative success of some of my fellow citizens. If you come from money, you certainly have a leg up. If daddy graduated from Harvard, and became a major donor, few would deny that you might get a so-called “legacy” admission. It’s no accident that Harvard has the largest endowment of any university, last year reaching $53.2 billion. But that nest egg has permitted Harvard – and similar universities – to admit students who could not otherwise afford to attend. (By the way, Harvard admits slightly more women than men, and enrolls whites and non-whites in roughly equal percentages. In a recent class, blacks made up 14 percent, about the same as their percentage of the country’s population.)

While everyone’s story is unique, most of us don’t come from inherited wealth. Let’s take mine. My father was born in 1906 on a small island off the West coast of Ireland. When he was two-years-old, his family emigrated to the United States, settling in the Pittsburg area. He had some college, but never graduated. He was variously a deputy sheriff, clerk in the county assessor’s office, elected councilman in Braddock, PA (where his family settled and where I was born), and manager of furnace company branches in Chicago and McKeesport, PA.

He died in 1950, when I was 12-years-old. My mother soon ran through the modest insurance money, and we ended up living in public housing. I was never without a job during my high school years. I set pins in a bowling alley; worked in a grocery store; and bussed tables and cooked at a Pittsburgh amusement park. My mother died when I was 18. By then, I was working at a steel mill. I then moved to Chicago and lived with my sister.

I did not get a legacy admission to Northwestern University. I worked during the day and attended school nights and weekends. I paid my own way, until I got drafted into the Army because I wasn’t going to school full time. After I got out, I was “privileged” to get part of my costs paid under the G.I. Bill. After I graduated, I started a long career in marketing and public relations. Having a degree from Northwestern certainly helped me along the way, but I flatter myself that I succeeded based on my own work and talents. And I don’t think I ever had a friend who’s success was due to family ties.

I don’t feel in the least guilty for being white. Nor should I; nor should anyone who has not actively discriminated against another race, even if that person’s ancestors held slaves. By the way, you would be forgiven for thinking that American had invented slavery. In 1787, when the Constitution was written, slavery was legal in most European countries, and widespread in most of the rest of the world. If we should blame anyone for slavery in this country, it is the British, who not only introduced it here, but profited most from it. And we shouldn’t forget that Britain came very close to recognizing the Confederate States, primarily to protect the source of cotton for their mills and tobacco for their pipes.

By the way, my family came to this country from Ireland because they saw no opportunity in a country exploited by the British for 200 years, and who let people die during the famine of the late 1840s. Now, nearly 175 years after the famine, a small number of Irish people still harbor the old hatred. But most have come to realize that living in the past is not the same as learning from it.

Copyright 2022, Patrick F. Cannon